The process of knowledge work is pretty simple.

- Decide what to build or fix.

- Assign a person to build or fix it.

- Provide the person with the support they need to build or fix it.

- The person(s) builds it or fixes it.

- Learn, reflect, and go back to step 1.

One of the key risks in knowledge work is the “Key man dependency” or “bus count”. The bus count is the number of people in the team at a bus stop that a bus would need to take out in order for the team to be unable to support the system. A “key man dependency” is where one or a very small number of individuals are vital for the development and support of a system, and if those people are not available, the system is at huge risk of failure, and is unable to be modified with the necessary time frame.

Two of the most likely causes of a “Key man dependency” are:

- An outside context event.

- Bad risk management.

Outside context events

In 2008, The financial crisis forced banks around the world to rapidly eject toxic derivatives businesses into “bad banks”, moth ball associated systems and reduce the development teams that supported them to minimal or zero membership. In 2010, the financial markets started to recover and the banks sought to bring the systems back on-line. The people that knew the systems were all key man dependencies. The situation was caused by events outside the control of the people managing the system, an outside context event.

Similarly, several people may leave an organisation at the same time leaving a key man dependency in their wake. Being unaware that people were unhappy and likely to leave is often a symptom of a failureship with a large power distance index. In a risk managed leadership culture, the leader should be aware of the needs and aspirations of their team, and the team should see the leader as a resource to help them find a new role either inside or outside of the organisation. This gives the leader time to resolve the potential key man dependency.

Bad risk management

In failureship cultures it is common to find systems supported by teams that contain one or more key man dependencies. Individuals hoard knowledge and experience with a system to gain personal advantage at the expense of the organisation. The advantages to the individual include, but are not limited to:

- Job security – Being known as a “key man dependency” means that a person is unlikely to be let go by an organisation.

- Money – Becoming a “key man dependency” means that a person is more valuable to an organisation and the organisation are prepared to pay a higher salary and bonus to the person.

- Status – Being known as the “go to” person to fix problems or get things done can lead to elevated status in the organisation, with senior stakeholders demanding trusted junior staff being present in important meetings simply because they are the only people “who know where the bodies are buried”.

- Promotion – Increased status leads to increased chance of promotion and ultimately more power in the organisation.

- Autonomy – Individuals who are key man dependencies are often given more autonomy as the organisation does not want to frustrate them by micromanaging them.

Without proper risk management, the dispositionality of a failureship organisation is for every individual in the organisation to become a “key man dependency”. Each individual will seek to become the only expert on a part of system, to be the “owner” of some critical component… To be the “go to” person to fix, build or enhance a particular item. An organisation with a risk averse failureship culture will focus entirely on the pursuit of value with no consideration of risk. Everyone in a failureship will be over utilized and have more work than they can do. Every task will be urgent with no time to address risk management through knowledge transfer. If Bob is the expert on component “X”, then all work on component “X” will be done by Bob, even if that means waiting for Bob to come back from holiday to fix it, build it or enhance it. Even better if Bob needs to be interrupted on holiday, thus reinforcing Bob’s status and value.

Without proper risk management, “key man dependencies” will naturally occur in an organisation with a failureship culture. Even worse, failureship cultures intentionally or unintentionally ENCOURAGE AND REWARD individuals who can establish themselves as a “key man dependency”.

Addressing “Key man dependencies” in a Risk Averse Failureship Culture

The dominant strategies for addressing “Key man dependencies” in a risk averse failureship culture are to wait for them to occur and then adopt one or more of the following strategies aimed at making sure that the individual who is a “key man dependency” does not leave the organisation:

- A senior leader explains to the person how important that they are and gives them special attention. (Increase JOB SECURITY and STATUS of the individual)

- A retention bonus is put in place to make sure the individual does not leave. (Increase MONEY). This bonus can then used by the individual to increase their package at a company they would move to thus increasing their disposition to leave the organisation as a move would permanently lock in the value of their unshared knowledge.

- A bonus is paid on the effective transfer of knowledge to other people in the organisation (Increase MONEY). The organisation has now introduced a bonus scheme to encourage people to become “key man dependencies”. Join a team, learn all the knowledge, behave badly so that the other key experts leave, receive bonus.

- The “key man dependency” is promoted. The individual is given more power and influence whilst doing the same job badly. The failureship has sent the strongest possible signal that the path to success is bad behaviour and incompetence.

- The individual is given more freedom and autonomy so that they can cause damage in another part of the organisation.

All of the intervention strategies to address “key man dependencies” in a risk averse failureship culture increase the risk of a key man dependency.

As an amusing aside, the WORST intervention I ever encountered was two decades ago. The original team who built a trading system had left the organisation leaving only two developers who understood how the whole system worked. The manager in charge of the system was one of those two developers and was post technical. Their manager pointed out that there was effectively only one developer left in the team who could make significant changes. The manager asked the developer out to lunch at an exclusive (and expensive) restaurant to explain how important the developer was to the organisation. At the end of the lunch, the manager also explained that there was no money and the developer would have to pay for their own lunch.

I leave you to your own conclusions as to whether risk averse strategies for managing “Key man dependency” will address the problem or encourage others to emerge.

Addressing “Key man dependencies” in a Risk Managed Leadership Culture

There are two concerns, first mitigating the “key man dependency” and second ensuring that “key man dependencies” do not occur in the future.

“Key man dependencies” normally arise because the organisation is risk averse, ignoring risk, and does not understand or value the mitigation of risk. The organisation seeks to push it on to another person or organisation regardless of whether that other organisation is competent to manage the risk. The most obvious example is organisations who engage consultancies with a track record of failure in a capability so that they can blame them when things go wrong.

Establish the priority of Risk

The first mitigation step is to establish the importance of key man dependency risk. The general priority of work for a team should be:

- Support. Ensure that the system operates as expected, and fix it when it doesn’t.

- Risk. Ensure that the system continues to operate as expected and can cope with any outage event.

- New investments.

Support work and New investments result in visible manifestations that stakeholders and manager can see. Risk is invisible. Stand in a street in front of two hotels. One is insured and the other isn’t. Can you tell the difference? Which one would you stay in? The only way to tell the difference is actively look for the attitude towards risk management (Does the bowl of M&Ms in the dressing room have any blue ones in it?).

Managing risk needs to be a primary concern of the organisation, not just support or new investments.

Mitigating a “Key man dependency”

The first thing that needs to be assessed is whether the “Key man dependency” was created by an “Outside context event” or “Bad risk management”.

If a team was very small and grew very fast due to unprecedented demand that the organisation could not control, the cause may be considered an “outside context demand”. If the team is large and/or the situation has been allowed to occur slowly over time, then the cause is likely to be “Bad risk management”.

If the “Key man dependency” is created by an “outside context event”, then the team need to be supported to resolve the situation. It normally means that forces outside the control of the team have forced the situation on them and the team needs be empowered and supported to push back on those forces. Another indicator of “Bad risk management” is an organisation that does not control its “Work in Progress” and takes on more work than it has capacity to deliver, often in “shadow backlogs” outside of the organisation’s normal prioritisation process.

If the “Key man dependency” is created by “Bad risk management”, then a management intervention of some kind may be necessary. It indicates that one or more individuals is not experienced enough in risk management for the responsibilities they have been given.

Simply put, the difference is whether the organisation should be allowed to manage the mitigation on its own with support, or whether the mitigation should be overseen by an external responsible party.

Specific tasks, skills and knowledge

“Key man dependencies” normally refer to the importance of an individual to the organisation. They do not refer to the specific tasks, skills and responsibilities that the person needs to perform. The first step to addressing a “key man dependency” is to identify the specific tasks, skills and knowledge that the person has that no one else in the organisation has. Often perception is different from reality and although the individual is the only person known to stakeholders and senior leaders, there may be many others in the team that are not known.

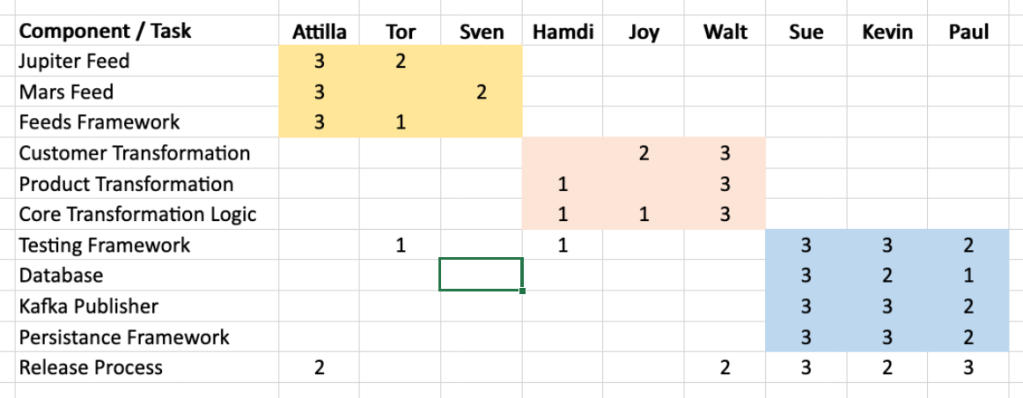

The skills matrix is a powerful tool for seeing this detail.

As well as seeing the current situation, it can be used to see the impact of people leaving or being unavailable.

It is important to identify all of the skills and tasks done in the team, especially the individuals who are identified as a “Key man dependency”. As well as working on components and tasks on the system, they may have “softer” skills and activities that require someone else to acquire as well. Some of these are skill based, some experience based and some require authorisation. Most will require practice to be competent. For example:

- Engage with stakeholders. (Skill & Practice)

- Represent organisation at steering committees and forums. (Experience, Practice & Preparation)

- Prioritize backlog. (Permission)

- Present at events. (Skill, Practice & Preparation)

- Submit budget. (Know process and people, and Experience)

- Escalate issue with Senior Management. (Experience)

There are often people in the team who can do the technical things, the key man dependency occurs because the individual is seen as the interface to the team. When they are away and another member of the team presents status at a steering committee, they do a bad job because they do not know what is expected. The stakeholders and senior manager lose confidence in the teams ability and assign competence to the missing “key man dependency”. They blame the “stand in” for not being able to do the task rather than blame the “key man dependency” for not training and preparing a “stand in”.

Once the detail of the missing skills have been identified, the team can address the skills liquidity (here and here). If the issue was an “outside context problem”, the team can be left to address the mitigation of the key man dependency. If the issue was “Bad risk management”, then an external agent should mentor and monitor the organisation as the risk is mitigated. At one organisation, management started by setting the quarter end target for someone to train two other people in support. They ignored the target and were subsequently removed from the support rota. They continued to fix issues. Eventually their access to the systems was revoked and they could not fix problems directly, they were only able to answer questions by those on support.

Motivating the risk management of “Key man dependencies”

In the mid 1990s I was shocked to hear that Bill Gates had said “If only one person knows about one part of an application, I sack them because I want to have control on when that issue needs to be addressed”. (Based on my very poor memory and I cannot find a reference). The message was clear, if you become a key man dependency, you will be sacked and other people will be forced to learn about what you do immediately.

Thirty years later I understand the wisdom of the statement. Bill Gates understood the dispositionality of large organisations towards “Key man dependencies” and instigated a policy that whilst appearing to to be incredibly risky actually ensured that “Key man dependencies” did not arise in the first place.

Inspirational as Bill Gate’s approach might be, a more measured approach might be to give the “Key man dependency” three months to mitigate the risk.

A key point to understand about “Key man dependencies” is that their value to the organisation is often related to the specific context of the organisation that they work in. In other words, they are probably paid above their market worth, more than other organisation would pay them for their general levels of skill and experience. Should they move to another organisation at the elevated level, their lack of skills and experience will probably be discovered during their probation period, especially risk management skills if they move to an organisation with a “risk managed” leadership culture.

External Support

The main value of the external support is to help the organisation establish the priority of risk management. They should help the organisation push back on new requests so that the “Key man dependency” risk can be mitigated.

Given the desire to look good to stakeholders at the expense of the wider organisation, the external monitor should ensure that the “Key man dependency” risk is removed before it is removed from the organisation’s risk register. Given the desire to remove the “unnecessary” constraint of the external support, individuals may be “encouraged” to claim to have greater proficiency than they actually have. In this case, the external monitor may require someone to prove their competence in a skill or at a task in the system (Paying down technical debt on their own is a good test).

It is generally good practice for organisations to require ALL employees to have a two week holiday every year. During the holiday the employee should have no contact with colleagues at the organisation or log into any systems. Regulators enforce this on employees of Financial services firms following the Sumitomo Copper Trading scandal where a rogue trader had not had a holiday for a decade and their market manipulation was only discovered when they were taken ill.

Failureship Counter Measures

As soon as a team is asked to create or to change the way they work to pay down “Key man dependency” risk, there will be a backlash from the organisation and some of their powerful stakeholders complaining that value is being delayed. Be ready for uninformed, fearful and powerful individuals intervening to protect their favorite “key man dependency” from being forced to share.

The Andon Cord

There is no Andon Cord. Senior Leaders instead should manage the negative space.

Instead of “Familiar faces in familiar spaces”, they should expect those familiar faces to step back and allow other faces to become familiar. Rather than “Why isn’t Bob at this meeting”, it should be “Why is it only Bob that is present at this meeting? Where are the other team members?”. Look for the negative space rather than always have the same positive space. You may discover that the story is not consistent.

Encourage teams to publish their skills matrix and support them by pushing back on stakeholders if they want to address knowledge transfer concerns. Once again, look for the negative space. Which teams have not published a skills matrix?

Leave a comment