One of the main strategies to avoid responsibility for delivery, and to avoid risk management of a process is to allow the system to be swamped by work, often shadow work that is not aligned to the goals of the organisation. Incompetent risk averse managers in a failureship culture engage in classic “child” behaviour of blaming stakeholders for forcing them to do more work than the system can cope with (“They made me do it, its not my fault”). In reality, it is exactly the fault of the person who allowed more work to be pushed onto the system than it can cope with in order to gain individual favour with a powerful stakeholder.

Unlimited “Work in Progress” in a Risk Averse Failureship Culture

Although the benefits of limiting “Work in Progress” to a sustainable level are well known, and well documented, less is said of the benefits to an individual in a risk averse failureship culture of IGNORING work in progress limits and deliberately allowing a system to be swamped with work.

Here are some of the benefits to an individual at the expense of the wider organisation of swamping a system with work in progress:

- The individual avoids accountability for delivery, or more accurately the failure to deliver on commitments, as they can always claim to be working on something of higher priority. When asked, each stakeholder will always claim that their items are higher priority than someone else.

- The individual can avoid doing things they do not want to do by claiming to be too busy.

- Being too busy avoids the need to share knowledge and skills leading to “key man dependencies“

- The individual can chose the work that benefits them the most, rather than focus on work that is most valuable to the organisation and aligned with the wider goals of the organisation.

- It makes it impossible to plan deliveries or track real progress of items. The focus is on starting things rather than completing things.

- The status of the individual is raised if others must wait for them in order to deliver a larger piece of work.

- Having too much work creates pressure to provide the individual with more resources and people, thus increasing their status which directly leads to promotions and pay rises.

- Having too much work allows individuals to hoard knowledge and withhold it from new team members creating the myth that it takes an extraordinary length of time to become effective with a system…. leading to more people and higher status.

- Being too busy means you get to say no to work you do not want to do.

- Being too busy means you are protected from your management who do not want to interfere with your work and be held accountable for your failure to deliver. Your risk averse management are afraid of being held accountable for you leaving the company.

- Being busy means autonomy and freedom.

Leaders need to address excessive work in progress if they are going to effectively risk manage in an organisation.

Addressing a swamp of excessive “Work in Progress” AT THE TEAM LEVEL

At the team level, addressing a swamp of work in progress is super easy and should take a MAXIMUM of one hour. It will take much longer than that if the team does not want to do it, often the excuse is they are too busy on important stuff that they are failing to deliver.

- The team create a Kanban board with a queue in front of each activity.

- The team put all the work they are currently doing on the Kanban board.

- Where people are working on more than one item at a time, they pick one item and move the rest of the work items back to the queue in front of that item.

- Prioritise the top few items in the Kanban board and either block the rest or move them off the kanban board and into the backlog.

- As capacity becomes available, unblock items or pull high priority items off the backlog.

Blocked items and items in the backlog are “Not started”. Items being worked on in the system are “Work in Progress”. Completed items are “Done”. In a system that is swamped, many items are actually blocked which means they are “Not started”, however it is not possible to see which items are really “Work in Progress” and which are “Not started” (Blocked). As the items are in the system is not possible to prioritise the work easily as it is under the “control” of the system. All we do by reducing the “Work in Progress” is provide genuine transparency over whether the items in the system are actually “Work in Progress” or “Not started” (Blocked or in the backlog).

Addressing a swamp of excessive “Work in Progress” ABOVE the team level

Addressing the swamp of excessive “Work in Progress” above the team level is much more complex as it means aligning the work of all teams involved in delivering something of value to a customer. In large complex organisations, many teams may be required in order to deliver something of value to a customer. The teams will often be involved in delivering parts of investments in several different value streams. In a large complex organisation, it is easy for one or a few teams to end up with a huge amount of demand for the current period of time which leads to swamping a team. Pushy and manipulative stakeholders find it easy to push teams to take on more work than they can cope with “The manager of your sister team said it was not much work” or “I can easily spin up a team to do it for myself”. The result is a team that is swamped…. especially if the organisation has weak senior leadership who cave whenever stakeholders apply a bit of pressure.

Capacity planning is a process for limiting work in progress across an entire organisation so that no team is assigned more work than it has the capacity to finish in a period. The process is deliberately simple by design as we know we are fighting against the dispositionality of the failureship culture which wants to remain in the swamp.

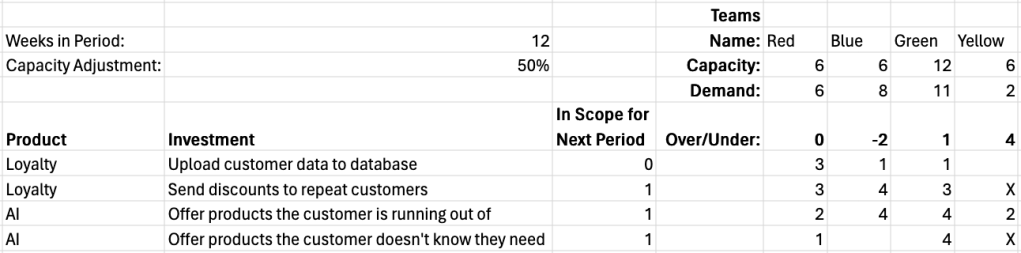

- List the candidate investments for the next quarter. Ensure that they are end to end investments that deliver value to a customer (internal or external).

- Identify all teams required to deliver the investment. (Do not forget legal, training, business change, operations etc.). Place an “X” against each team.

- Get each team to provide a SWAG estimate (Sweet Wild Asses Guess) in team weeks. SWAGs should take a few minutes to determine AT MOST.

- Calculate the capacity of each team (Number of teams * Number of weeks in period * Capacity Adjustment * [100% – PercentageOfBusinessAsUsual])

- Calculate demand on each team by summing all the SWAGs from Step 3 that are in scope

- Compare demand with capacity (Over/Under).

- Bring all stakeholders together to agree which items will be descoped from the next period.

- Descope items until the demand is less than or equal to the capacity FOR ALL TEAMS!

- Publish organisation wide backlog for the next period.

- When stakeholders want to add items to the backlog, use the capacity plan to identify which items will not be delivered as a result.

- At the end of the period, review the order in which items are delivered.

Capacity Plan as the “Work in Progress” Andon Cord

Applying “Work in Progress” limits at the organisation level is an exercise in creating organisational alignment. All of the stakeholders agree the best backlog for the organisation and commit to it.

Senior leaders can use the Capacity Plan as an Andon Cord. They can look at it to understand the state of the organisation, especially as it relates to whether it is swamped with “Work in progress”. From the capacity plan, leaders have transparency into the organisation’s product and delivery, and use it as a map to work out where they want to visit in GembaLand.

- Delivery of value – The investments should articulate the business value they will deliver by satisfying the needs of a customer segment. For example “Grow engagement by making it easier and quicker for repeat customers to migrate from one product to another.” Where the business value (engagement), customer segment (repeat customers) or customer need/job to be done (quicker and easier migration) are not clear, the leader can go to the Gemba and ask for clarification. If it is not clear about the value to the customer, the risk is that the investment may not deliver value.

- Parts that do not deliver value – Often the investment describes a part of a solution for a customer. For example “A teabag” instead of a “Cup of tea”. This means that the investment needs to be combined with other investments before it delivers something that satisfies the needs of a customer. (Above, “Upload customer data to database” is a tea bag as it is only part of the solution)

- Missing teams – It is difficult to spot when the owner of an investment has missed a team they need to deliver. The capacity plan does make it easier though as similar investments might need capacity from “The legal team to review contracts”, “The business change team to provide training”, “The architecture team to review designs”. When one set of investments need such teams but a similar set do not, it makes it easier for the leader to spot the missing teams. Another opportunity to visit GembaLand.

- Missing customers – In large organisations, many products and services are delivering value to internal customers. In such cases, if an internal customer is not included in the investment, then it means the product or service is being shipped to shelf and will not be generating value until the customer consumes it.

- Missing SWAG estimates – This normally means that the owner of the investment has not reached out to the owner of the team to explain what the investment is about and what they need from them. This helps leaders identify investment owners who need to improve their communication. The lack of a SWAG estimate may also indicate a huge amount of uncertainty on the part of the team as to how they are going to deliver what is required. (See Yellow team above)

- Not descope items – Often the owner of a number of investments is the same as the owner of the team. If the demand is greater than the capacity, then the investment owner needs to descope items so that the team can deliver in the period. If the investment and team owner does not descope items, there is a risk that they do not take limiting their work in progress seriously and is a strong candidate for taking on too much work and not delivering on their commitments. They are also a hot contender for running a shadow backlog. (See Blue team above)

- Increase capacity – If a team owner has more demand than capacity, they address the shortfall by increasing their capacity. If the demand is 20 team weeks of work, they increase the capacity to 20 or 21 team weeks. As with “not descoping items”, these team owners do not value limiting work in progress and are candidates for not delivering, and/or running a shadow backlog. (See Green team above)

- Not engage in prioritisation – Some investment owners (or stakeholders) do not engage in prioritisation. The consequence is that they will then try to force their investments on the teams. Senior leaders should use this behaviour to identify individuals who are putting their own personal success ahead of the success of the wider organisation. The root cause of this behaviour is sometimes due to an increased sense of importance, however it is more likely due to a performance management or reward system (bonuses) etc. that is not aligned with the goals of the organisation.

- Ignore capacity plan – Some investment owners and stakeholders ignore the capacity plan and demand that their work is done by the teams. The wrong-order-o-meter will identify these at the end of the period. It can also be used during the period, however it is better if senior leaders keep close contact with teams that have constrained capacity so that any interference can be addressed swiftly.

- Ignore order of work – Teams might ignore the order of work due to their own preference, or because they are pressured to do so by an important stakeholder. Once again the wrong-order-o-meter will help leaders spot this behaviour. However generally speaking teams tend to want to do the right thing, so if it is not a rogue stakeholder, the wrong-order-o-meter will show that teams are blocked from working on the higher priority work due to either internal or external constraints.

- Take on new work – If pressured, teams will take on new work during the period. Once again, the wrong-order-o-meter will help but it is better if senior leaders reduce the power distance index so that teams feel comfortable raising issues about stakeholders behaviour.

One of the keys to successfully limiting work in progress is to ensure that the period is a quarter or less. At the end of the quarter, the organisation can reflect on the number of investments (“Wholes”) that are delivered, and the number of parts delivered (“Each team’s contribution to an investment”). It is likely that the capacity adjustment will need to addressed, probably reduced. It will also be clear where teams are working on shadow backlogs as they will have completed work that is not within scope on the capacity plan.

This makes the capacity plan an ideal Andon cord for leaders to identify where they should go to the Gemba and possibly stop the line.

April 28th, 2024 at 10:39 am

More gold, how do you think about sizing of work in terms of granularity? E.g. teams favour pulling work from a prioritised “whole” item (epic or similar grouping of work as an investment)

If teams have spare capacity and still deliver on the prioritised items, should teams review with product roles for new priority or are you supportive if they spend time on technical debt / quality improvements / risk reduction etc.

Doing SWAG estimates makes sense for a course grain work item. What are your thoughts on the sequencing or scheduling of work e.g. if a team completes work before it is needed or they finish it before another team has done their part of the whole, it can fail integration testing and create more rework, assumes tight coupling, which is pretty common.

Having a supporting session between tes on the regular would be helpful to align on sequencing, scheduling and coordination.

April 28th, 2024 at 10:56 am

Really great questions. I’ll respond to some as blog posts over the next few weeks. The quick answers:

Teams should be working collaboratively to deliver “wholes”. Regular Scrum of Scrum meetings for the “Whole” should prevent a team delivering its “part” well ahead of the other teams. Completed “Parts” that do not form a “whole” are to be avoided as they lead to all sorts of risks. A team will hundred of feature flags in production is sitting on huge risk.

Teams should be cleaning up technical debt as part of their normal jobs. Sometimes they will encounter a huge chunk that needs prioritising. The product owner should be prioritising the pay down of big chunks based on when it will be needed, not because it offends someone’s sense of design.